-

Superconductivity is achieved through macroscopic phase coherence; the charge carriers are Cooper pairs. In absence of an external magnetic field and applied current, the behavior of these Cooper pairs can be described by a single wave function

$ \psi = {\psi _{\rm{0}}}{e^{i\varphi }}$ , and the phase is uniform over the space. When applying an external field but still below a certain threshold, a screening current will be established at the surface, which prohibits the entering of magnetic field, that is so-called Meissner effect. When the external field is larger than this threshold, the magnetic flux will penetrate into the sample, forming the interface of superconducting and normal state regions. According to the sign of this interface energy, we can categorize superconductors into type-I (positive interface energy) and type-II (negative interface energy). Most superconductors found so far are type-II in nature. Due to the negative interface energy in type-II superconductors, the penetrated magnetic flux will separate into the smallest bundle, namely the quantum flux line, with a quantized flux${\varPhi _0} = h/2e$ (h is the Planck constant and e is the charge of an electron). There are weak repulsive interactions among these vortices, thus usually they will form a lattice, called mixed state. When applying a current, a Lorentz force will exert on the flux lines (vortices) and will make them to move, this will induce energy dissipation and the appreciable feature of zero resistance of a superconductor will be lost. By introducing some defects, impurities or dislocations into the system, it is possible to pin down these vortices and restore the state of zero resistance. The study concerning vortex pinning and dynamics is very important, which helps not only the understanding of fundamental physics, but also to the high power application of type-II superconductors. This paper gives a brief introduction to the vortex dynamics of type-II superconductors.-

Keywords:

- high temperature superconductors /

- flux dynamics /

- cuprate superconductors /

- iron based superconductors

[1] Ginzburg V L, Landau L D 1950 Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 20 1064

[2] Wen H H, Zhao Z X 1996 Appl. Phys. Lett. 68 856

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[3] Cheng W, Lin H, Wen H H, et al. 2019 Sci. Bull. 64 81

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[4] Wen H H, Li S L, Zhao Z X 2000 Phys. Rev. B 72 716

[5] Dew-Hughes D 1974 Philos. Mag. 30 293

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[6] Griessen R, Wen H H, Van Dallen A J J, et al. 1994 Phys. Rev. Lett. 72 1910

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[7] Van Bael M J, Temst K, Moshchalkov V V, et al. 1999 Phys. Rev. B 59 14674

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[8] Bean C P, Livingston J D 1964 Phys. Rev. Lett. 12 14

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[9] Morozov N, Zeldov E, Konczykowski M, Doyle R A 1997 Physica C 291 113

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[10] 张裕恒 2007 超导物理(合肥: 中国科学技术大学出版社)第三版 第94−96页

Zhang Y H 2009 Superconductivity Physics (Hefei: Press of University of Science and Technology of China) pp94−96 (in Chinese)

[11] Bean C P 1962 Phys. Rev. Lett. 8 250

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[12] Wen H H, Wang R L, Li H C, Guo S Q, Yin B, Zhao Z X 1996 Phys. Rev. B 54 1386

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[13] Anderson P W, Kim Y B 1964 Rev. Mod. Phys. 36 39

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[14] Fisher M P A 1989 Phys. Rev. Lett. 62 1415

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[15] Feigel’man M V, Geshkenbein V B, Larkin A I, et al. 1989 Phys. Rev. Lett. 63 2303

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[16] Malozemoff A P, Fisher M P A 1990 Phys. Rev. B 42 6784

[17] Maley M P, Willis J O, Lessure H, et al. 1990 Phys. Rev. B 42 2639

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[18] Thompson J R, Civale L, Marwick A D, Holtzberg F 1994 Phys. Rev. B 49 13287

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[19] Schnack H G, Griessen R, Lensink J G, Wen H H 1993 Phys. Rev. B 48 13181

[20] Wen H H, Schnack H G, Griessen R, Dam B, Rector J 1995 Physica C 241 353

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[21] Blatter G, Feigel’man V M, Geshkenbein V B, Larkin A I, Vinokur V M 1994 Rev. Mod. Phys. 66 1125

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[22] Koch R H, Foglietti V, Gallagher W J, et al. 1989 Phys. Rev. Lett. 63 1511

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[23] Wen H H, Zhao Z X, Wijngaarden R J, Rector J, Dam B, Griessen R 1995 Phys. Rev. B 52 4583

[24] Bardeen J, Stephen M J 1965 Phys. Rev. 140 A1197

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[25] Kwok W K, Paulius L M, Vinokur V M, et al. 1998 Phys. Rev. Lett. 80 600

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[26] Houghton A, Pelcovits R A, Sudbø A 1989 Phys. Rev. B 40 6763

[27] Le Blanc M A R, Little W A 1960 Proc. Seventh Int. Conf. Low Temp. Phys. p198

[28] Pippard A B 1969 Philos. Mag. 19 217

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[29] Larkin A I, Ovchinnikov Yu N 1979 J. Low Temp. Phys. 34 409

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[30] Campell A M, Evetts J 1972 J. Adv. Phys. 72 199

[31] Li S L, Wen H H 2002 Phys. Rev. B 65 214515

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[32] Giamarchi T, Le Doussal P 1994 Phys. Rev. Lett. 72 1530

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[33] Giamarchi T, Le Doussal P 1995 Phys. Rev. B 52 1242

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[34] Nishizaki T, Naito T, Okayasu S, et al. 2000 Phys. Rev. B 61 3649

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[35] Kokkaliaris S., Zhukov A A, de Groot P A J, et al. 2000 Phys. Rev. B 61 3655

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[36] Fruchter L, Malozemoff A P, Campbell I A, et al. 1991 Phys. Rev. B 43 8709

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[37] Wen H H, Zhao Z X, Griessen R 1995 Sci. Chin. A38 717

[38] Hoekstra A F T, Testa A M, Doornbos G 1999 Phys. Rev. B 59 7222

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[39] Blatter G, Ivlev B I 1994 Phys. Rev. B 50 10272

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[40] Nagaoka T, Matsuda Y, Obara H, et al. 1998 Phys. Rev. Lett. 80 3594

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[41] Jin R, Paranthaman M, Zhai H Y 2001 Phys. Rev. B 64 220506

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[42] Wang L M, Sou U, Yang H C, et al. 2011 Phys. Rev. B 83 134506

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[43] Dorsey A T, Fisher M P A 1992 Phys. Rev. Lett. 68 694; Wang Z D, Ting C S 1991 Phys. Rev. Lett. 67 3618; Vinokur V M, Geshkenbein V B, Feigel’man M V, et al. 1993 Phys. Rev. Lett. 71 1242; van Otterlo A, Feigel'man M, Geshkenbein V, et al. 1995 Phys. Rev. Lett. 75 3736; Ao P 1998 J. Phys. Condens. Matter 10 L677

[44] 闻海虎 2006 物理 16

Wen H H 2006 Physics 16

[45] 闻海虎 2006 物理 111

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

Wen H H 2006 Physics 111

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

-

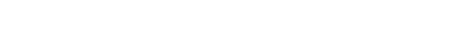

图 1 II类超导体的 (a)磁化强度曲线和(b)磁感应强度随外磁场的变化示意图. Hc1和Hc2分别是下和上临界磁场, Meissner和Mixed state分别表示迈斯纳态和混合态区域

Figure 1. Schematic plot of (a) magnetization and (b) magnetic induction with the variation of external magnetic field H. Hc1 is lower critical magnetic field and Hc2 is upper critical magnetic field. Meissner state and Mixed state are labelled as “Meissner” and “Mixed state” respectively.

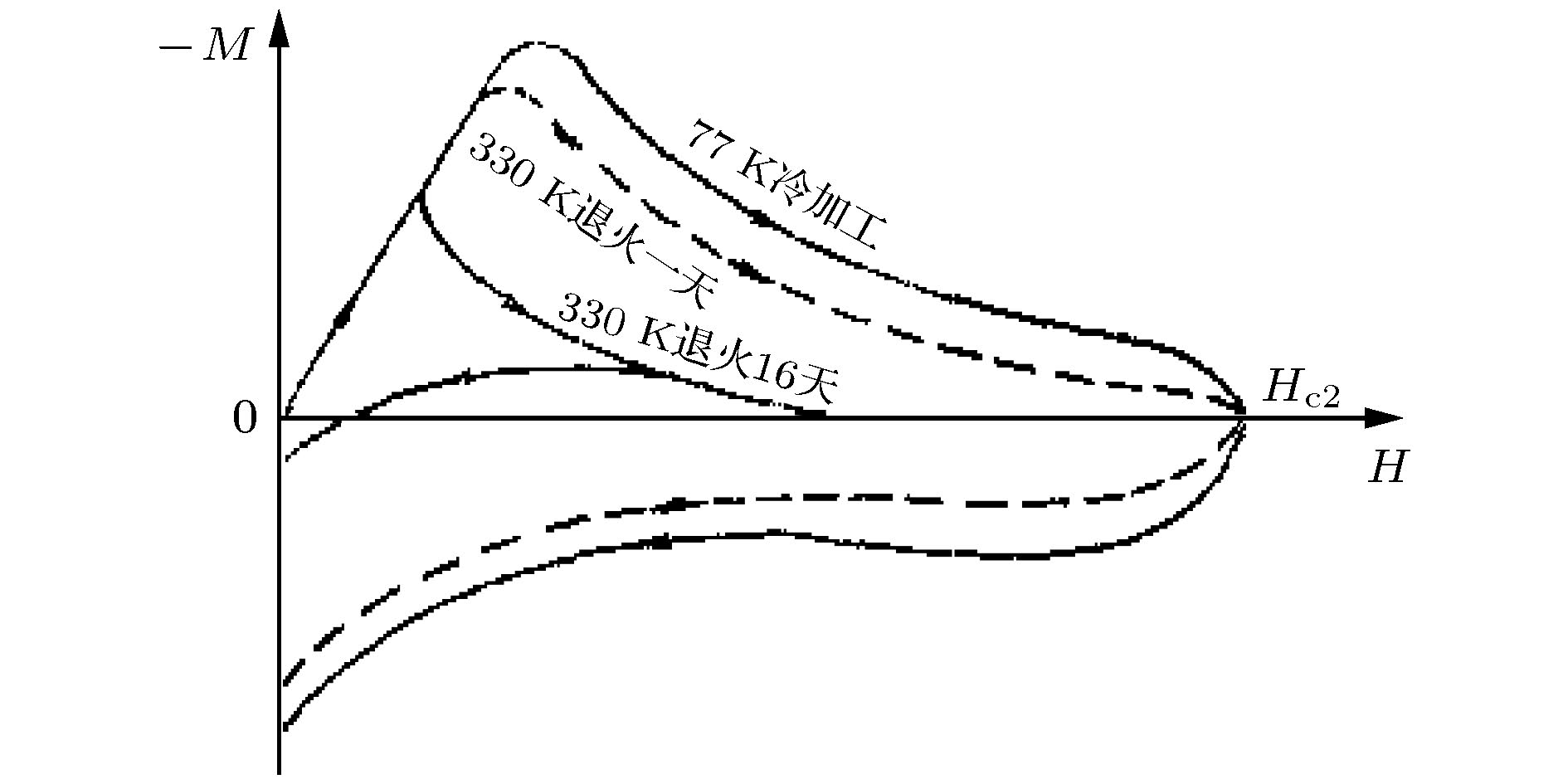

图 2 II类超导体NbTi的磁滞回线. 在冷加工的样品中, 由于存在很多缺陷和位错, 会有磁通钉扎中心的存在, 因此磁滞回线就变成不可逆的

Figure 2. Magnetic hysteresis loops (MHLs) of type II superconductor NbTi. In the cold-annealed samples, MHLs are irreversible in a large field region due to the existence of defects and dislocations which form the flux pinning centers.

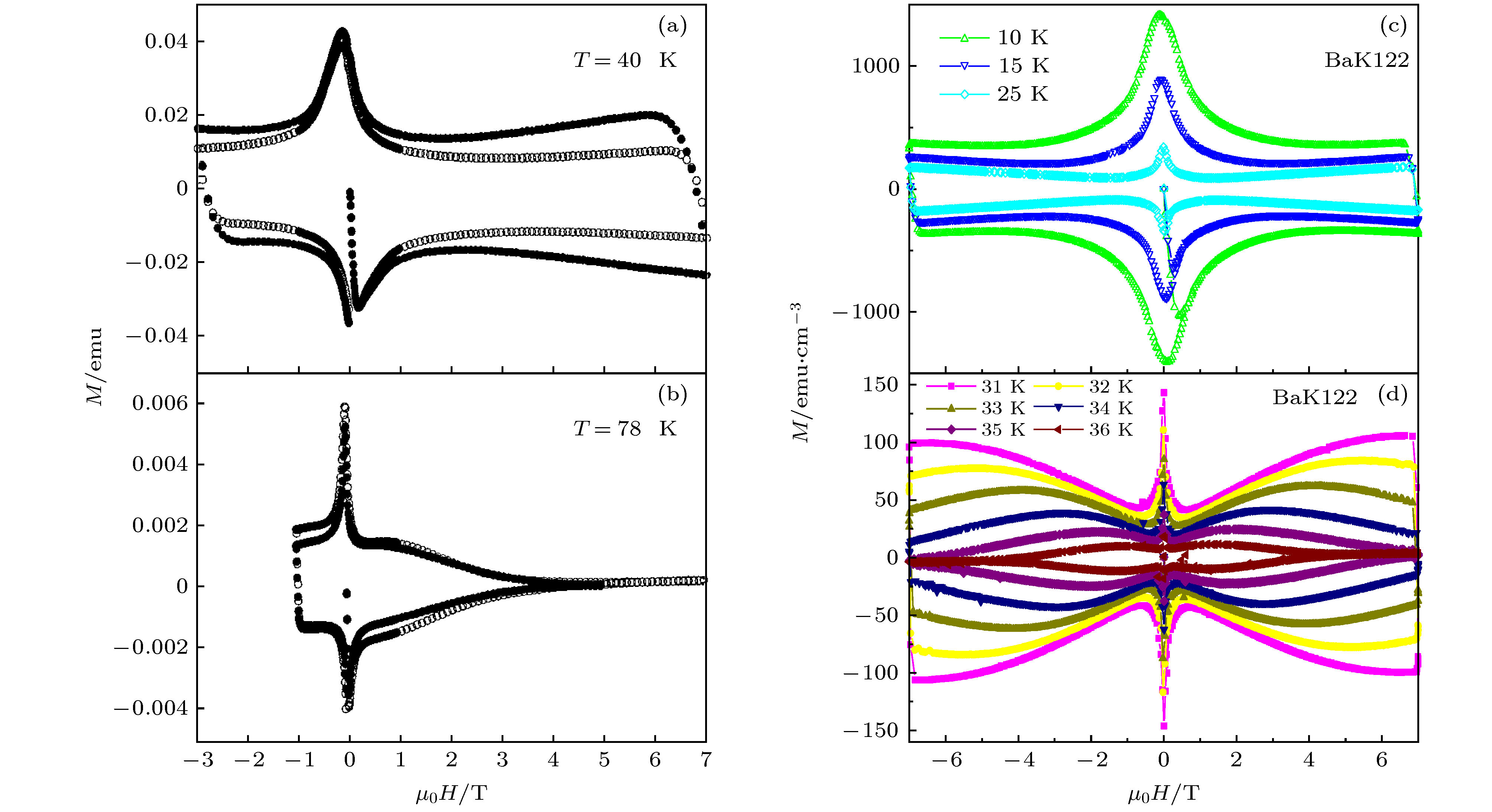

图 3 (a), (b)铜氧化物超导体YBa2Cu3O7–δ在40和78 K的磁滞回线, 实心点和空心点分别对应的是氧缺位较多和在氧气中后处理的样品; (c), (d)铁基超导体Ba0.6K0.4Fe2A2在不同温区的磁滞回线[2]

Figure 3. (a), (b) MHLs of cuprate superconductor YBa2Cu3O7–δ with oxygen-deficient (solid point) and oxygen-rich states (hollow point) at 40 and 78 K; (c), (d) MHLs of iron-based superconductor Ba0.6K0.4Fe2A2 at different temperatures[2].

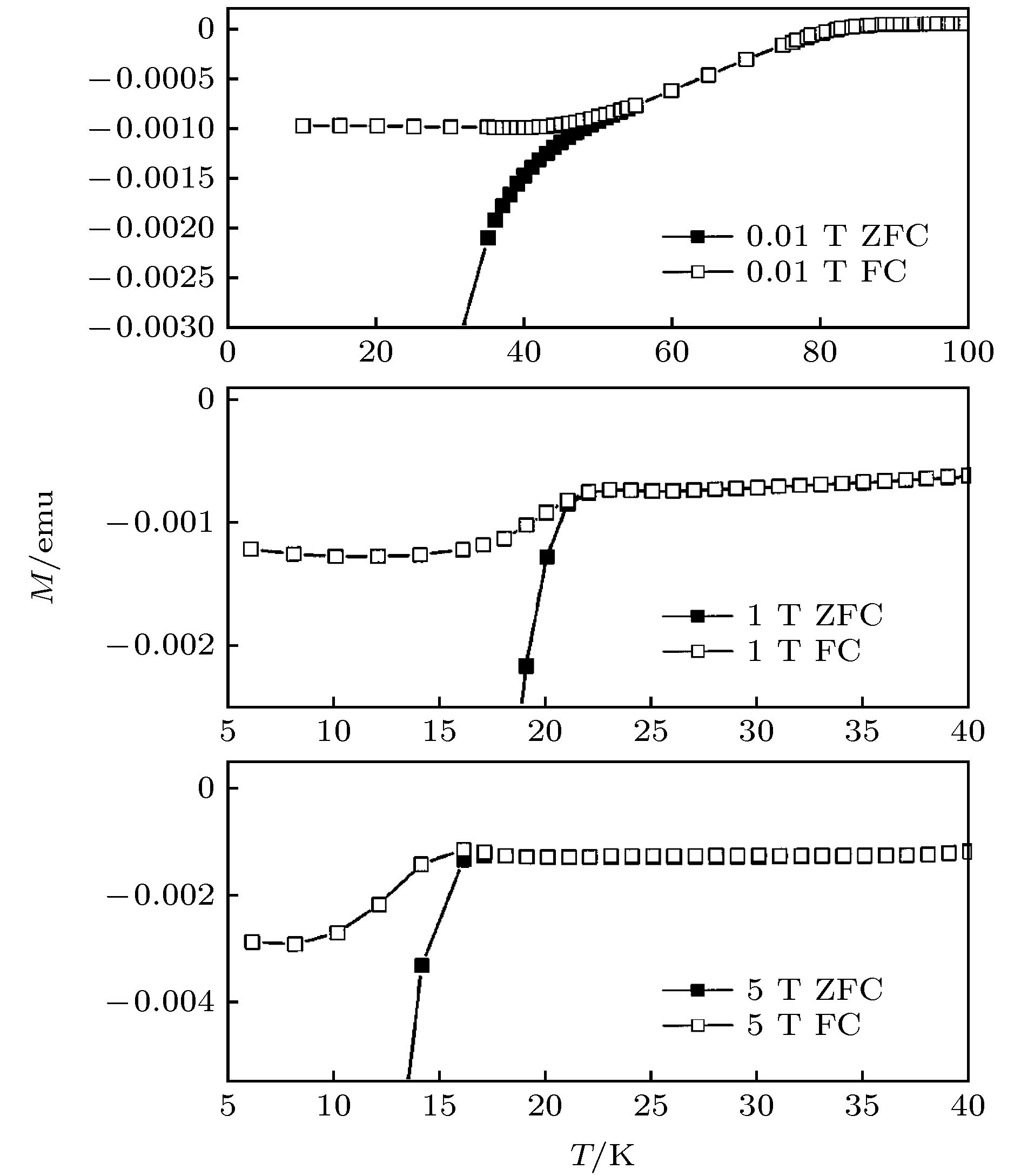

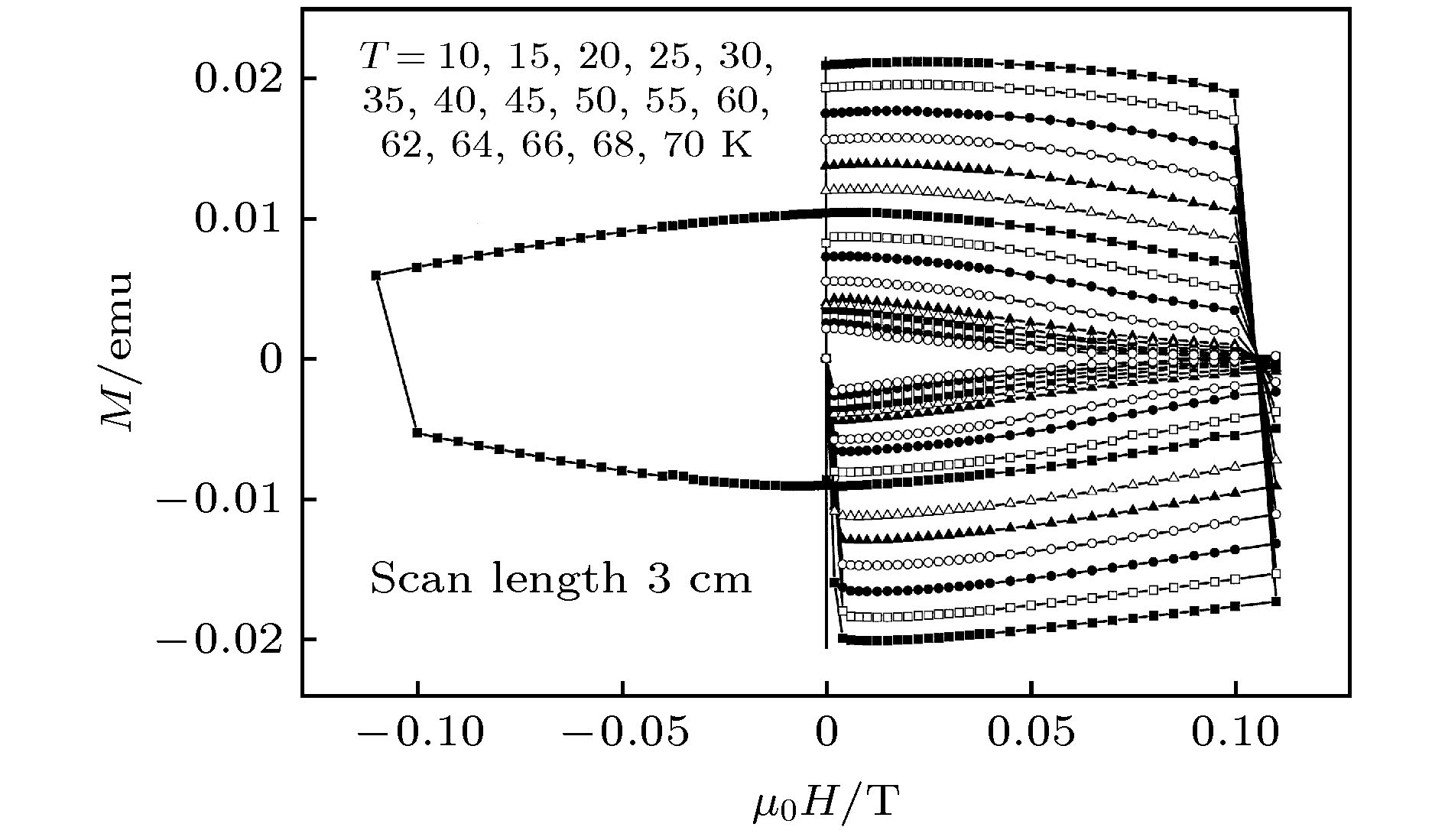

图 9 Tl2Ba2CaCu2O8超导薄膜在外磁场平行于c-轴(膜厚度方向)时的磁滞回线[12]. 这里大部分的磁滞回线显示的是正磁场的部分, 只有40 K的数据显示了一个完整的正负磁场的磁滞回线

Figure 9. MHLs of Tl2Ba2CaCu2O8 superconducting thin films with external magnetic field parallel to c-axis[12]. Most of the MHLs are only shown for the part of positive magnetic field; except for that at 40 K it shows a complete MHL which includes both positive and negative field parts.

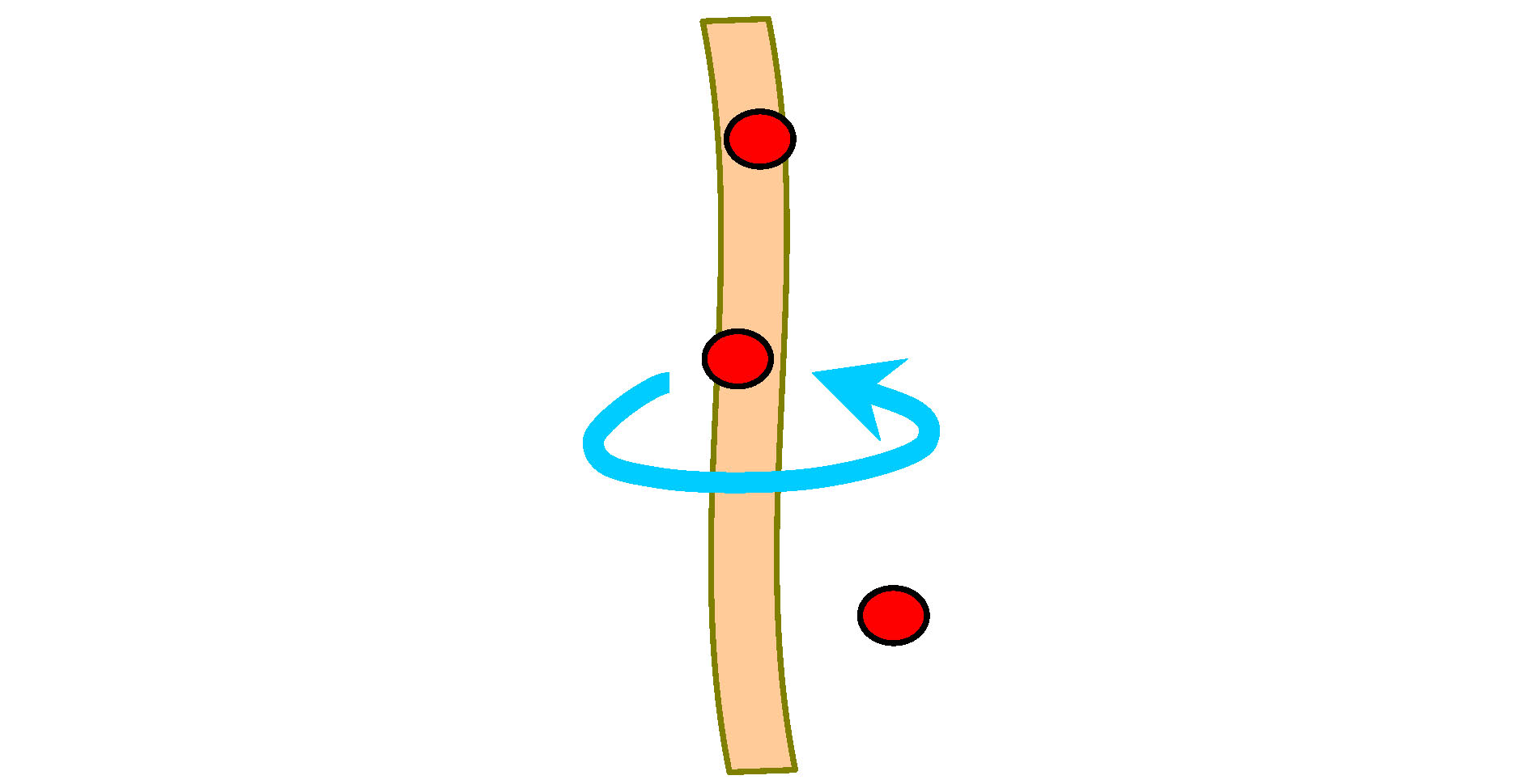

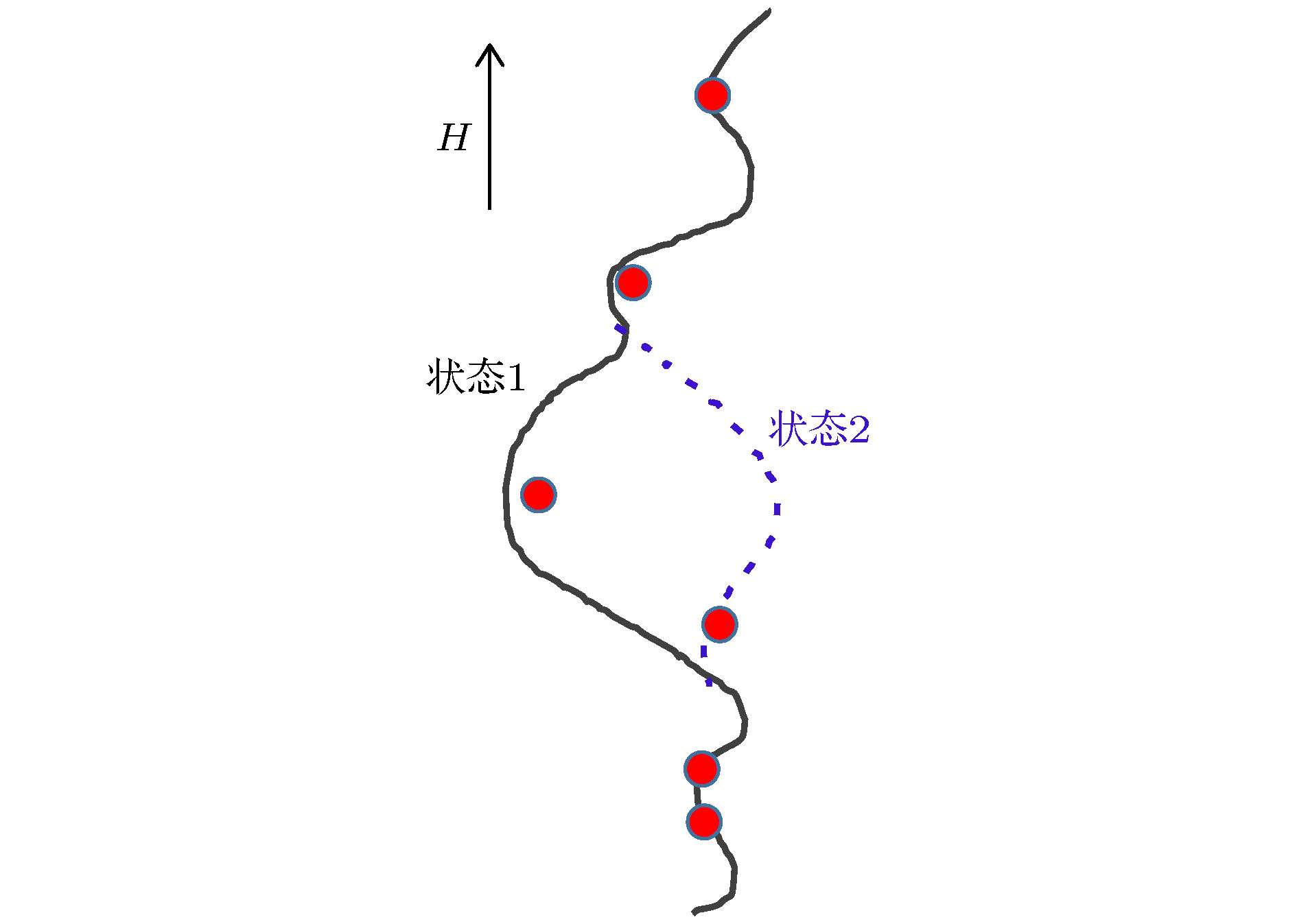

图 11 磁通蠕动示意图. 红色圆点是磁通钉扎中心, 黑色粗线是磁通的初始状态, 在洛伦兹力作用下, 磁通向右边运动, 其中用蓝色虚线标识的一段磁通运动到下个钉扎点, 然后其他段再逐次蠕动

Figure 11. Schematic of flux creep. Red points represent flux pinning centers and black thick line is the initial flux state. Under the action of Lorentz force, the flux starts to move toward right direction. During the process, the blue dashed part firstly moves to next pinning center and then other parts creep gradually.

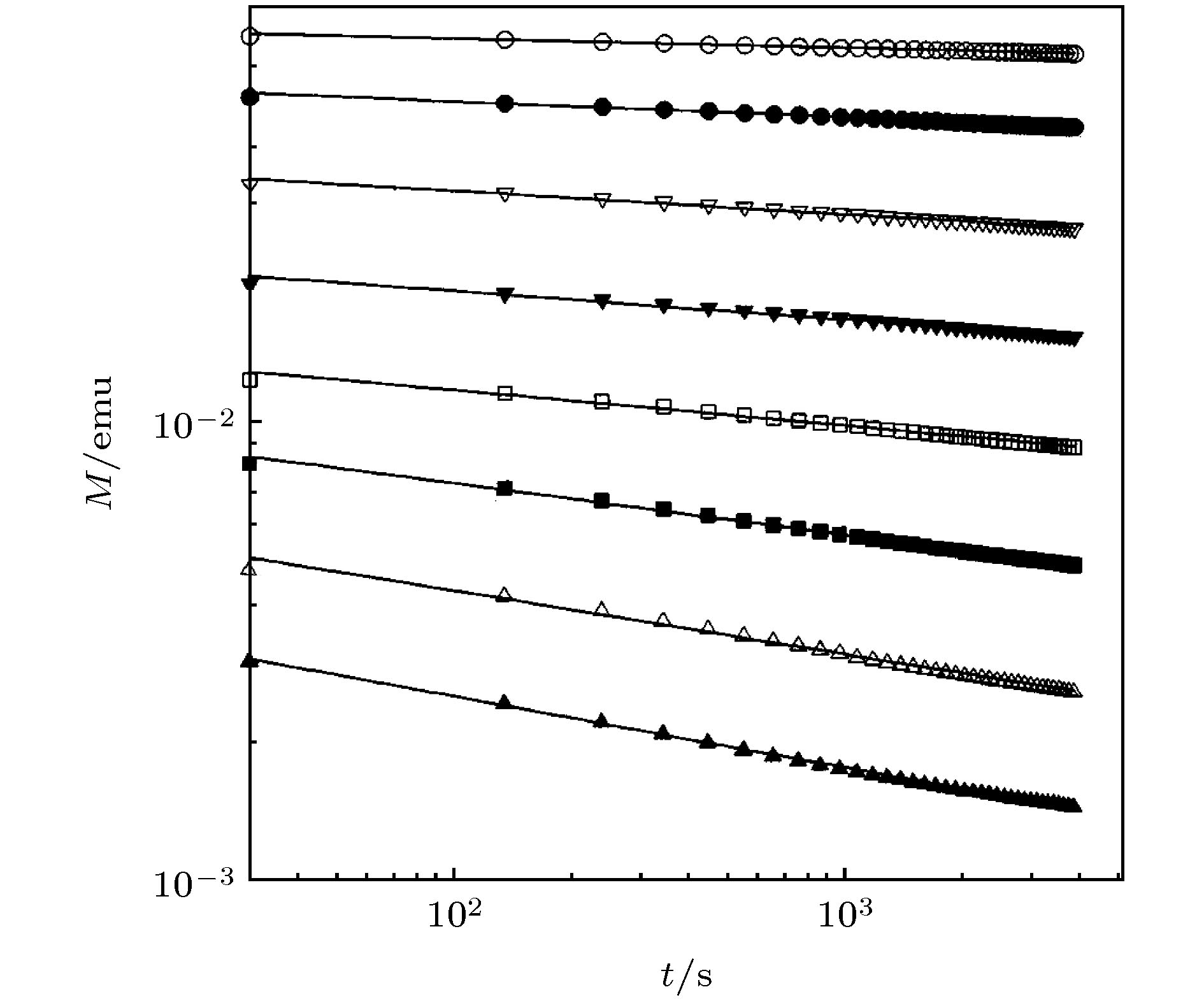

图 12 Tl2Ba2CaCu2O8超导薄膜中测量到的超导体磁化强度(大约正比于超导体瞬态临界电流) 随时间的变化[12]. 测量磁场是0.4T, 测量温度是4.5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40K (从上往下)

Figure 12. Magnetization of Tl2Ba2CaCu2O8 superconducting thin films (approximately proportional to time-variation of the transient critical current in superconductor)[12]. The measurement was taken under a magnetic field of 0.4 T, and at 4.5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40 K (from top to bottom)

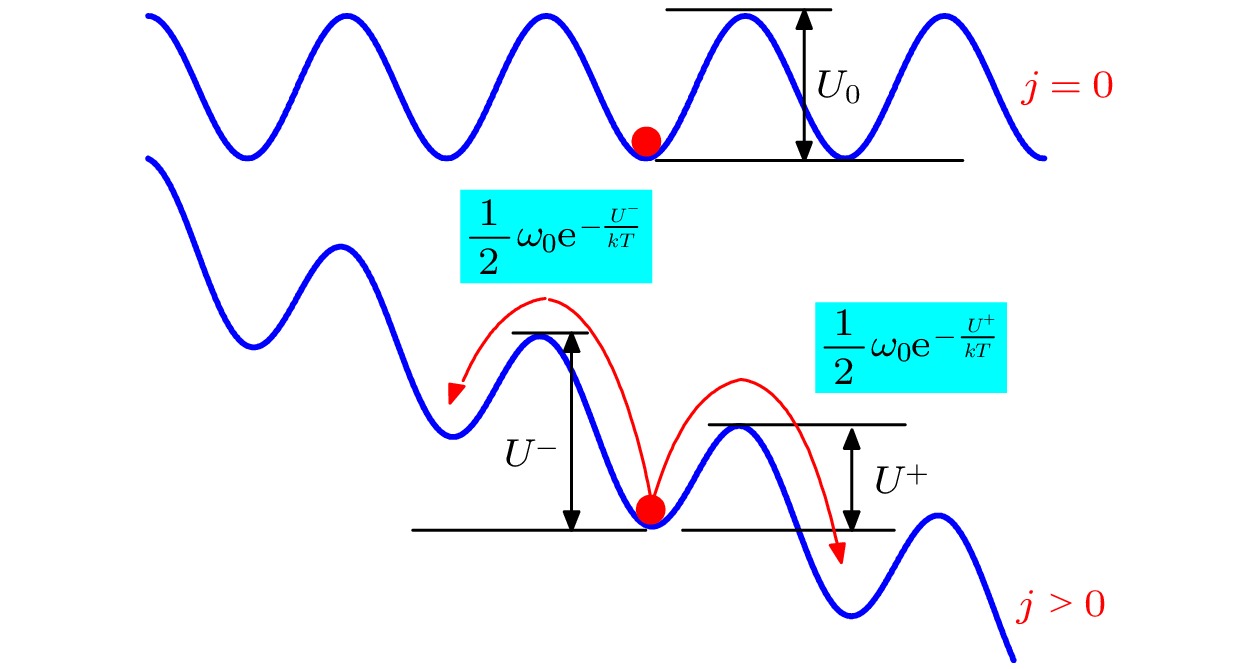

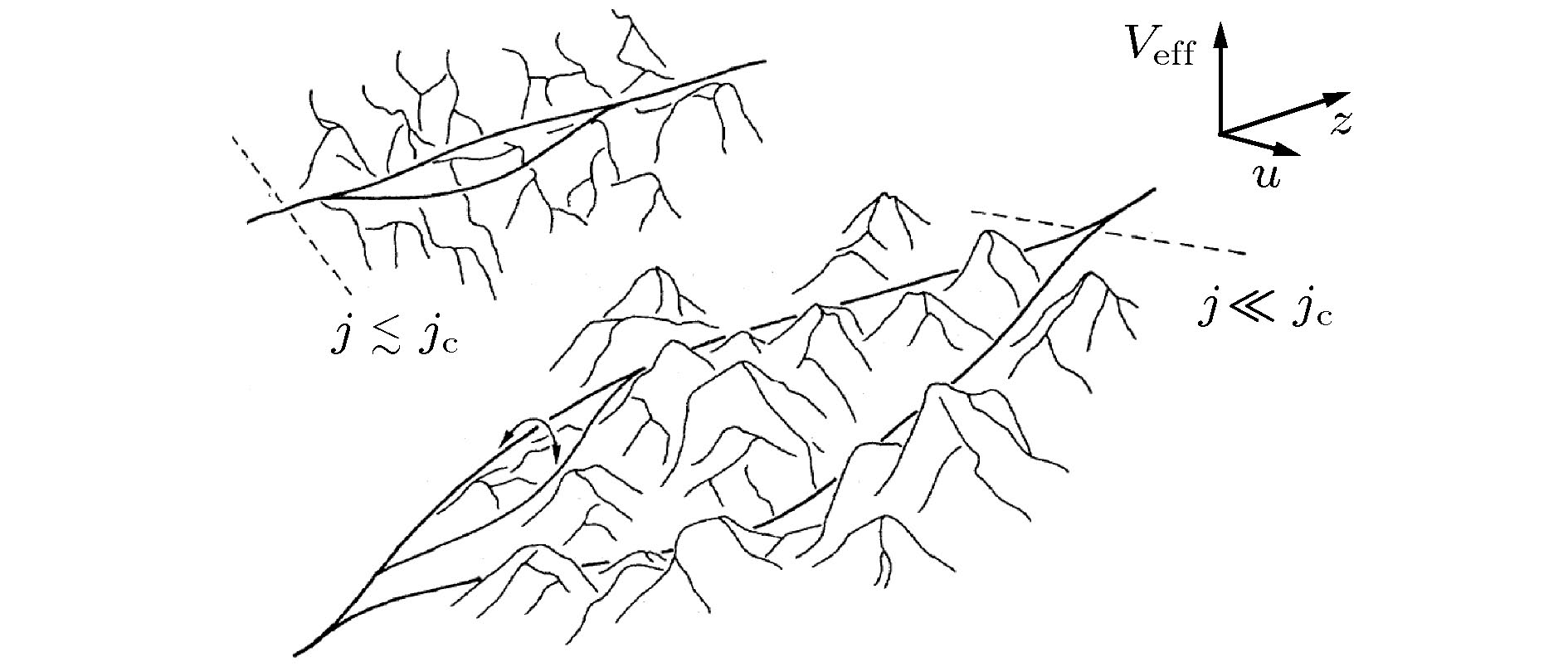

图 13 集体钉扎情况下, 非线性U(j) 关系来源示意图. 当外电流j与临界电流jc接近时, 最可能跳跃的长度是一个较短的集体钉扎长度Lc,此时的热激活能比较小. 当外电流远远小于临界电流时, 最佳的跳跃方式是一段较长 (长度为L) 的磁通束从外电流中获取更大的能量, 然后跳跃一个相对较高的势垒U, 而

$L/{L_{\rm{c}}} > {j_{\rm{c}}}/j$ . 因此热激活跳跃的最可能的长度或体积将会随着洛伦兹力(或电流)的变化而非线性变化. 该图取自文献[21]Figure 13. Schematic of the origin of nonlinear U(j) relation in collective pinning model. When external current j is close to critical current jc, the optimized jump length is a short collective pinning length Lc. If j is far less than jc, the best way to jump is a long (L-length) flux line or bundle to obtain sufficient energy from external current j and then jump a relatively high barrier, and

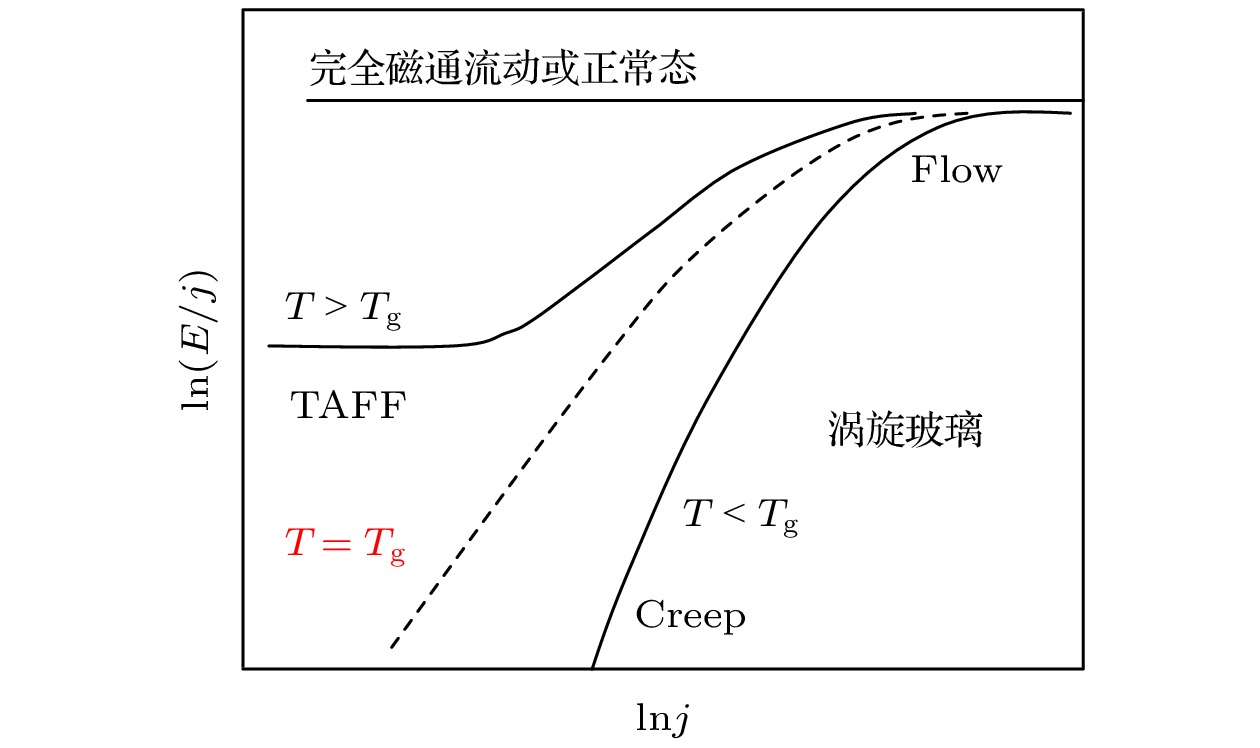

$L/{L_{\rm{c}}} > {j_{\rm{c}}}/j$ . Therefore, the optimized hopping length or volume of thermally activated flux motion will change along with the Lorenz force (current). The figure is adopted from the literature[21].图 14 涡旋玻璃图象下的耗散行为. 在T = Tg, 发生了磁通固态的二级融化相变. 在融化温度以上, 有一个线性电阻存在, 其耗散可以用热激活磁通流动模型描述. 融化温度以下对应着涡旋固态, 尽管磁通位置的空间有序不再存在, 但是超导的长程位相关联仍然存在, 因此系统线性电阻为零. 类比于自旋玻璃态, Fisher把它定义为涡旋玻璃态[14]

Figure 14. Schematic of dissipation in vortex glass picture. A second-order melting phase transition occurs at T = Tg. A linear resistance exists above the melting temperature, and its dissipation can be described by thermally activated flux flow model. There is vortex solid state below the melting temperature. Even though the order of flux lattices no longer exists, the long-range superconducting phase correlation still exists, so the linear resistance of the system is zero. As an analogous to spin glass, Fisher defined it as vortex glass[14]

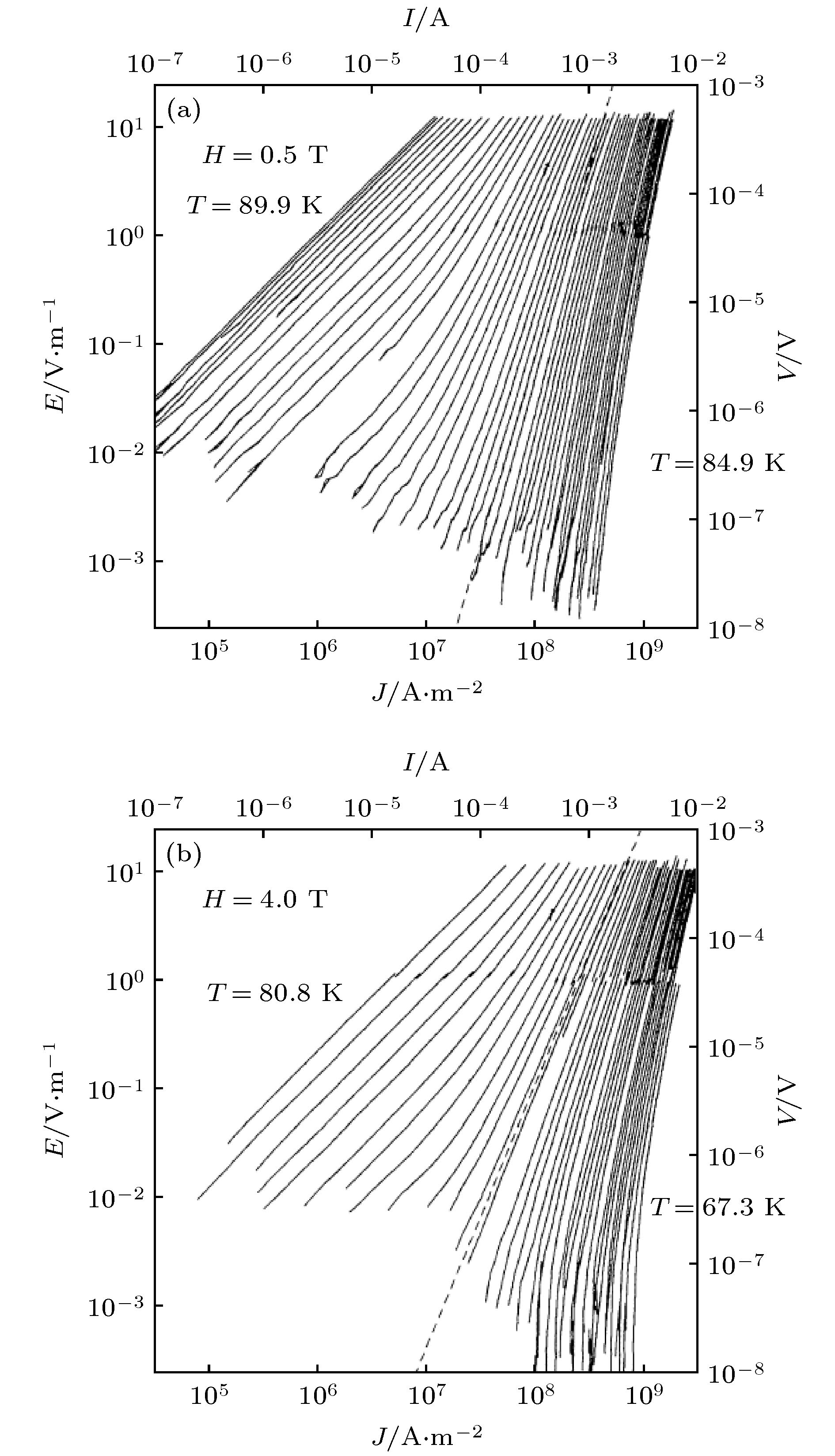

图 15 验证涡旋玻璃最早的数据之一. 磁场为0.5 T (a) 和4 T (b) 时在YBCO薄膜制备的微桥上测量到的E-j耗散关系. Koch等[22]将不同磁场下测量到的数据利用二级相变的标度率进行标度发现其临界指数均接近z ≈ 5, ν ≈ 1.7

Figure 15. One set of the earliest data to verify vortex glass. E-j dissipation relation measured on YBCO thin film micro-bridge at 0.5 T (a) and 4 T (b). Koch et al.[22] scaled the data measured under different magnetic fields by using the scaling of second-order phase transition, and found that the critical exponents are close to z ≈ 5, ν ≈ 1.7.

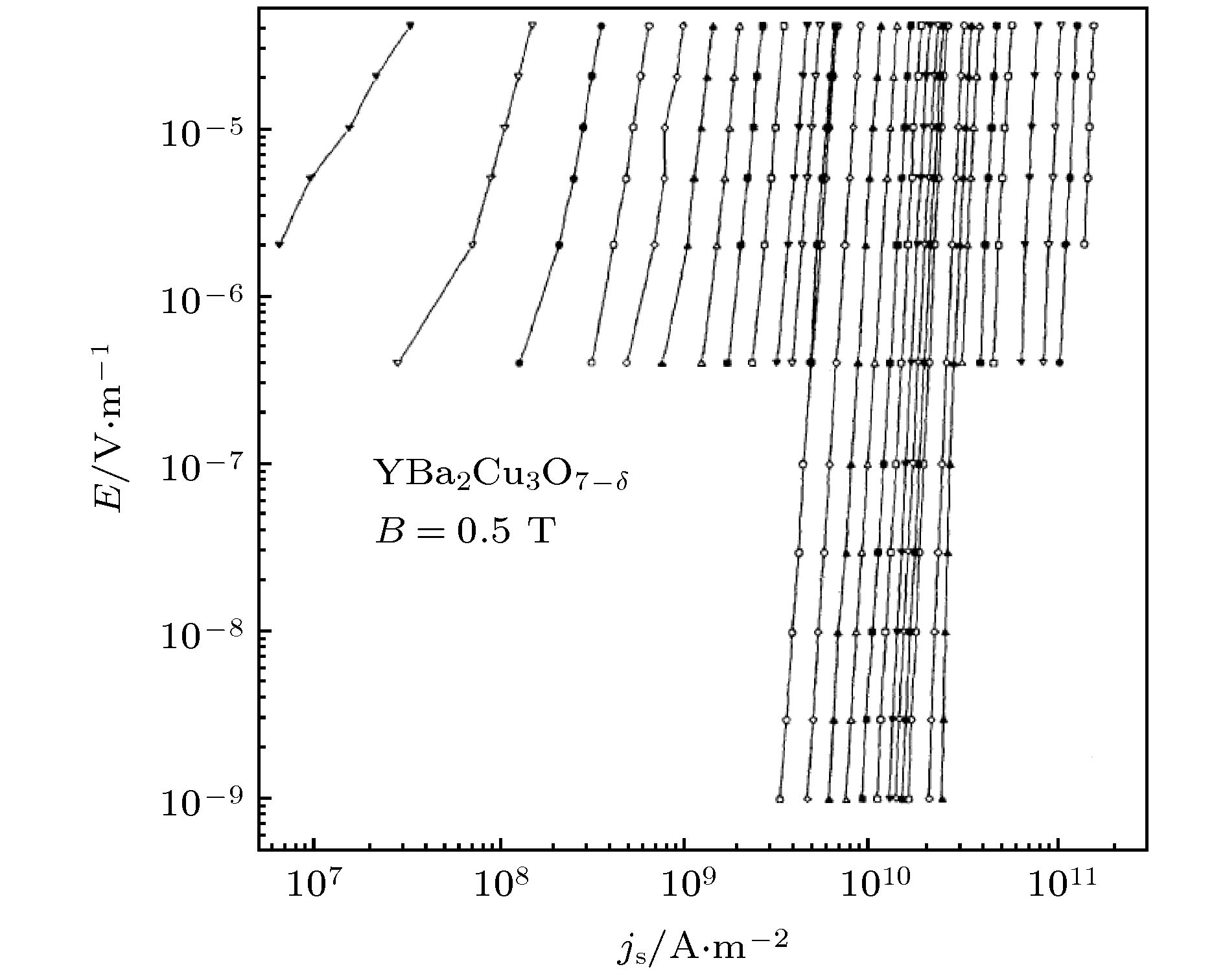

图 16 YBa2Cu3O–δ薄膜在宽电场范围内的耗散关系. 上部分为电输运测量结果, 下半部分为磁感应测量到的磁化强度弛豫结果. 经过分析, 即便在非常低的电场下(10–9 V/m), 其耗散也非常低, 而没有出现一个恒定大小的电阻, 磁通运动耗散仍然可以用涡旋玻璃模型来描述, 因此进一步证明了涡旋玻璃的存在

Figure 16. Dissipation relation in a wide range of electric field of a YBa2Cu3O7–δ thin film. The upper part is the result of electric transport measurement, and the lower part is the result of magnetization relaxation measured by magnetic induction. After analysis, even in very low electric field (10–9 V/m), the dissipation is very low, and there is no constant resistance. The magnetic flux dissipation can still be described by the vortex glass model, and therefore, the existence of vortex glass is further proved.

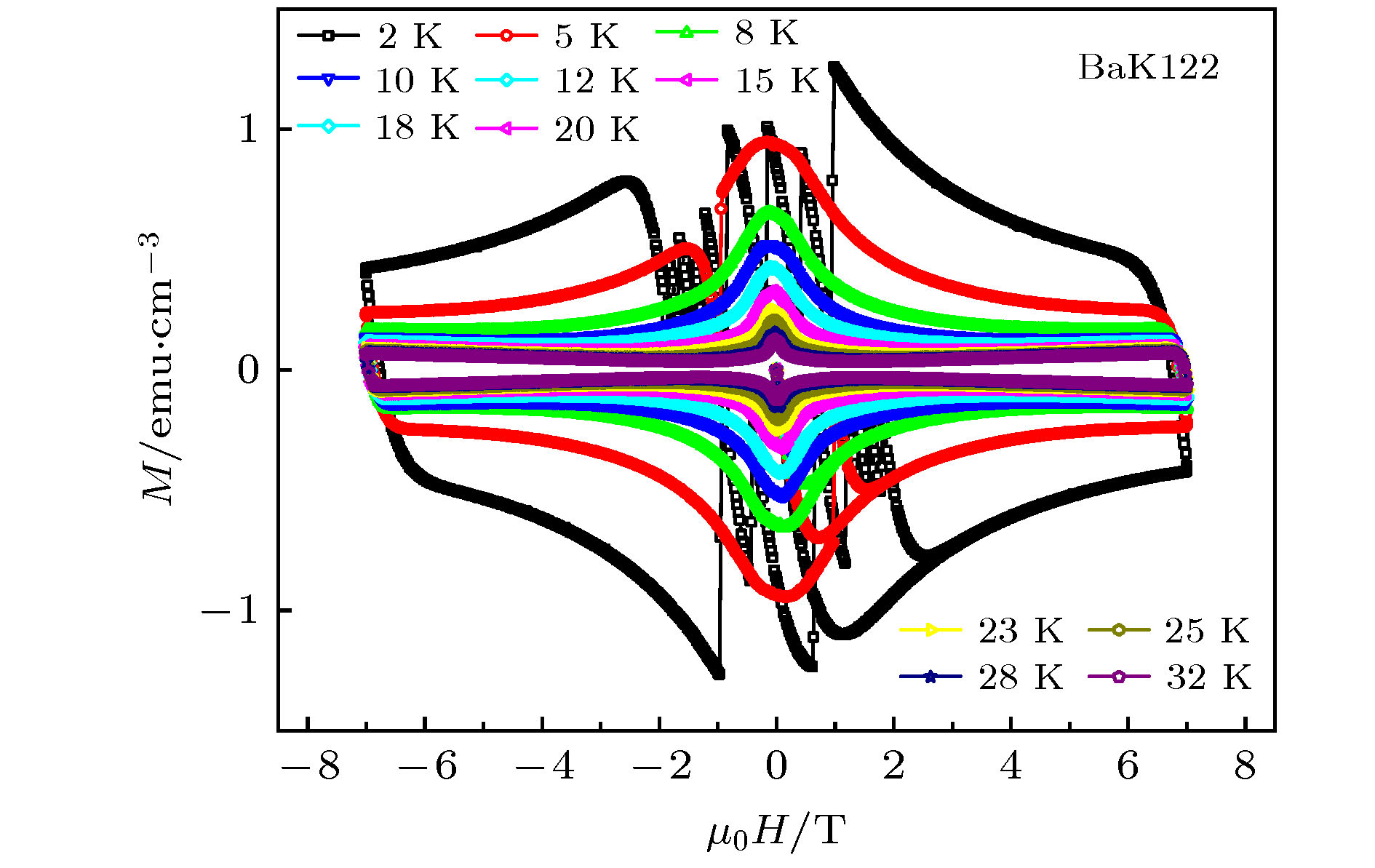

图 17 铁基超导体Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2在不同温度的磁滞回线. 在2和5 K的磁滞回线上面, 出现了一些不连续的跳变, 这是磁通跳跃所造成的雪崩效应的结果. 磁通跳跃过程可以用磁光实验直接看见[3]

Figure 17. MHLs of Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2 at different temperatures. There are discontinuous jumps on the MHLs of 2 and 5 K, which is the result of avalanche effect caused by flux jump. The process of flux jump can be seen directly by magneto-optical experiment[3].

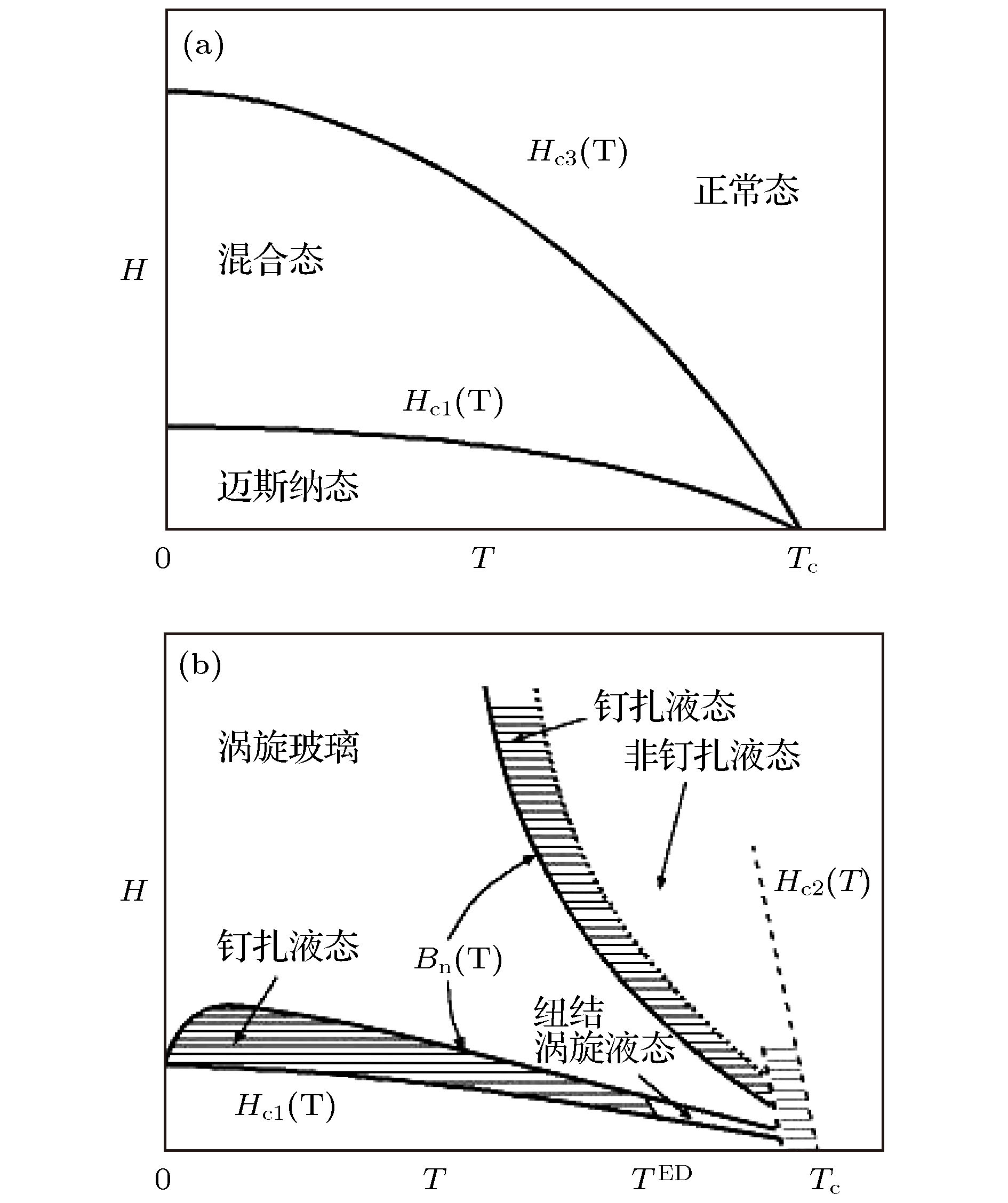

图 18 (a) 常规超导体或三维性较强超导体的磁场-温度相图. 磁通运动的不可逆线与上临界磁场很接近; (b) 二维性较强的磁场-温度相图, 在上临界磁场以下的一个很大区域内出现磁通液态, 没有临界电流. 在更低的温度,会出现一个涡旋玻璃态, 其磁场和温度的上边界线对于不可逆线. 有理论预言在Hc1附近, 由于磁通密度很低, 磁通线间的相互作用很弱, 因此也可能出现一个磁通液态. 但是实验上对于这个钉扎液态不好界定, 因为没有线性耗散的出现

Figure 18. (a) H-T phase diagram of conventional superconductors or superconductors with stronger three-dimensional properties. The irreversible line of flux motion is close to upper critical magnetic field; (b) H-T phase diagram of superconductors with stronger two-dimensional properties. There is flux liquid and no critical current in a large region below upper critical magnetic field. In the region at lower temperatures, there is a vortex glass state with zero linear resistance. The upper boundary of this vortex glass state is the irreversibility line Hirr(T). It is predicted that there may be a vortex liquid state near Hc1 as the flux density is very diluted and the interaction between flux lines is very weak. However, it is difficult to prove the existence of this pinned liquid state near Hc1 experimentally as there is no linear dissipation.

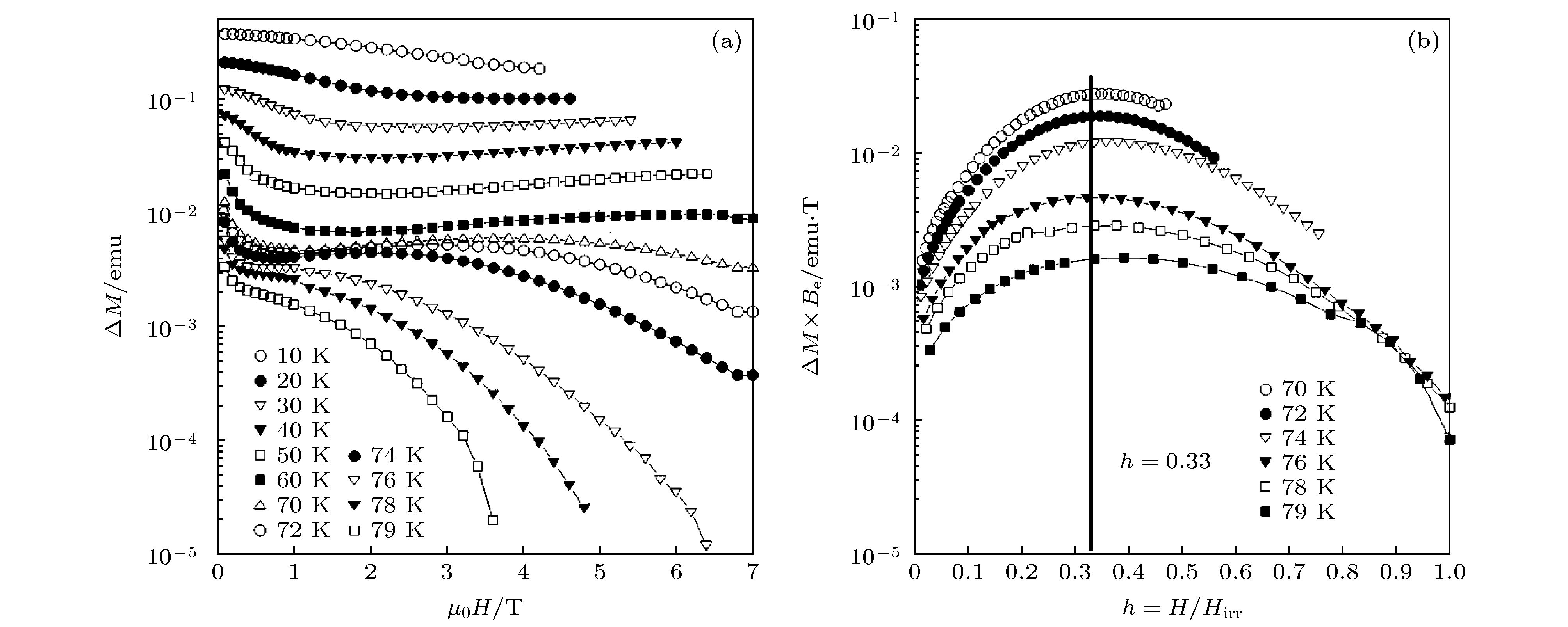

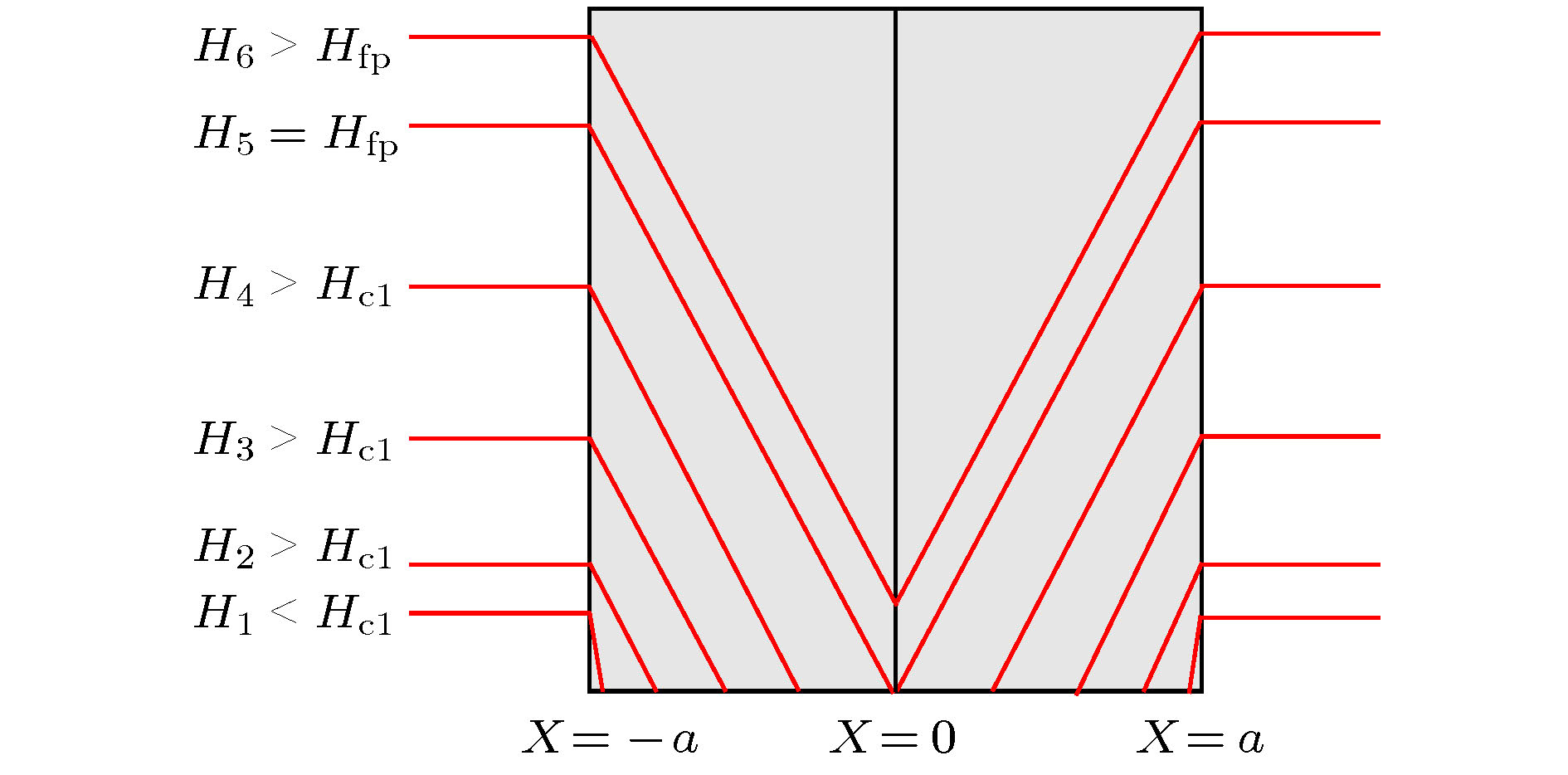

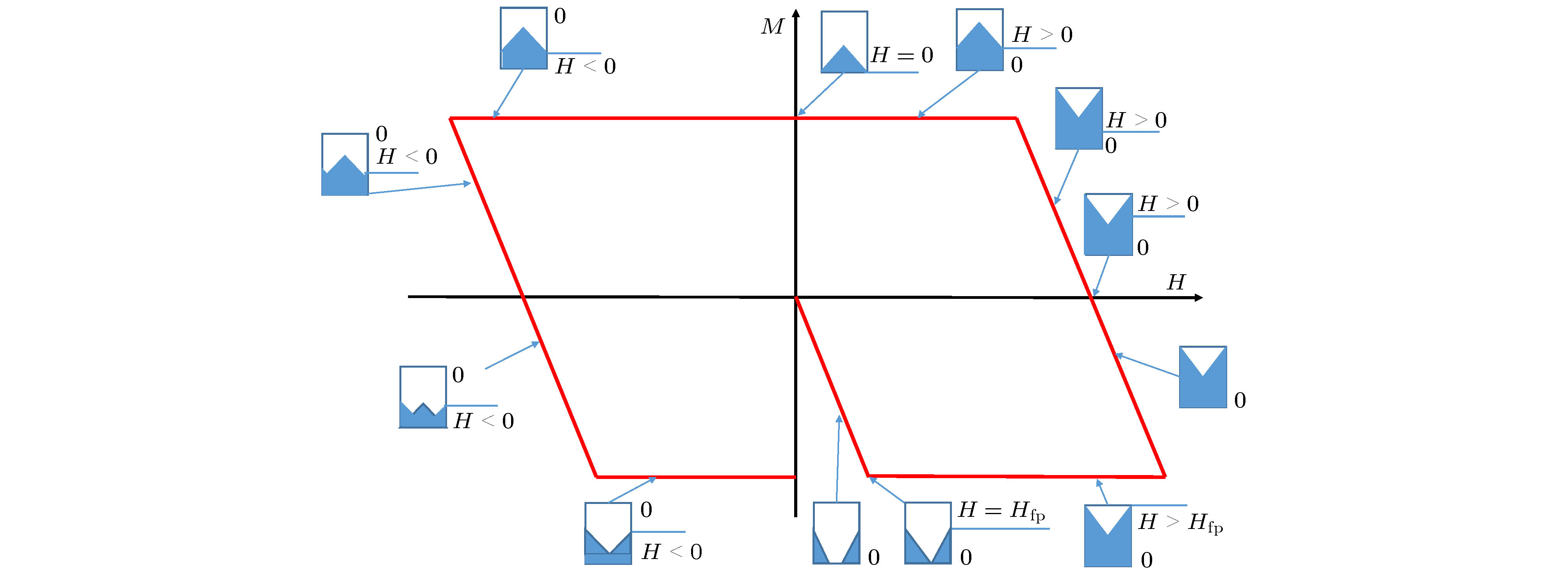

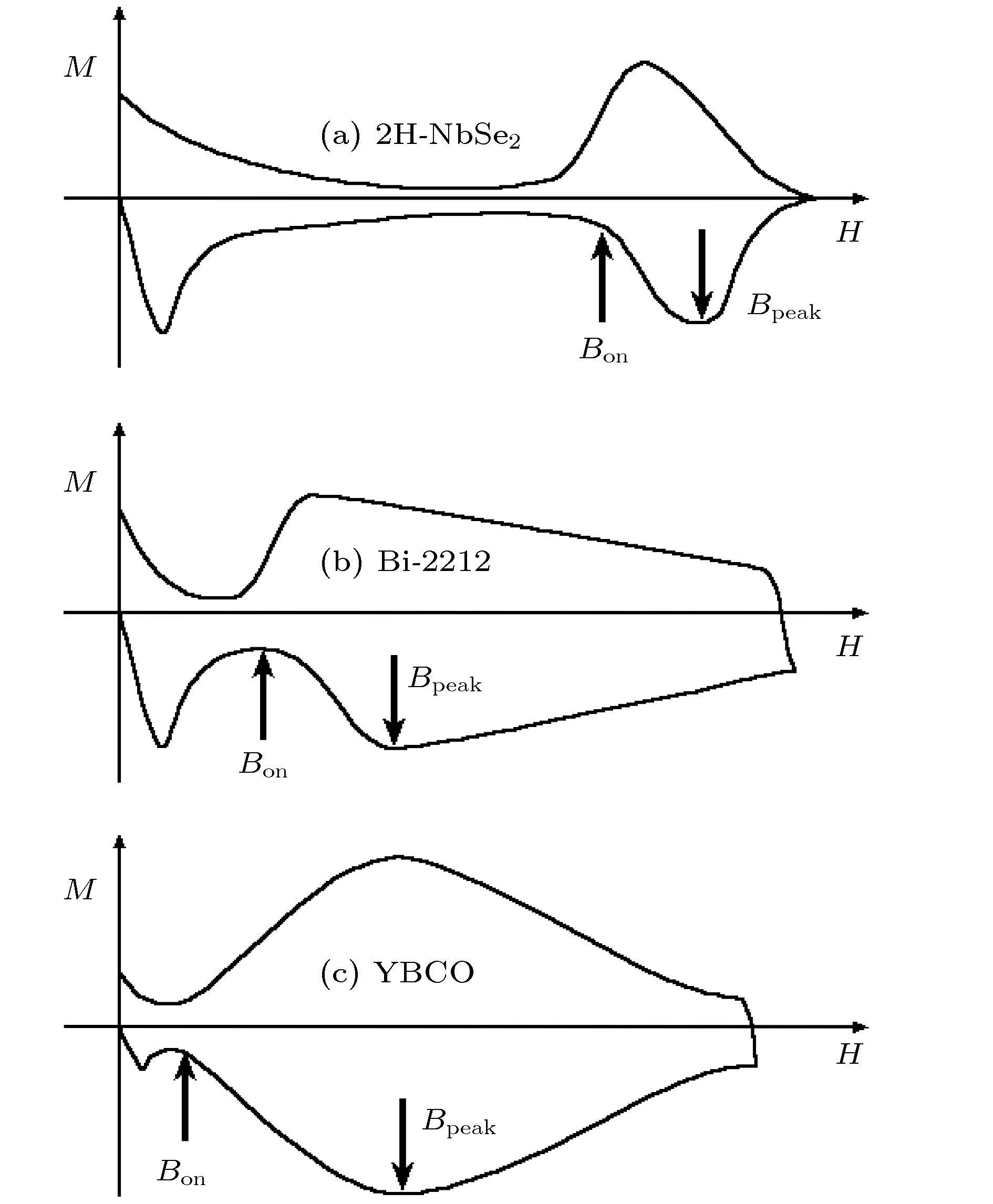

图 19 三种不同类型II类超导体磁滞回线的第二峰效应(a) 2H-NbSe2超导体中的磁滞回线, 在上临界磁场附近发现一个尖峰; (b) 高温超导体Bi-2212中的磁滞回线, 在较低磁场的时候(200−500 Oe), 发现一个较陡的磁化强度第二峰; (c) 高温超导体YBCO中出现的第二峰, 其可以出现在很高的磁场值, 但是仍然远低于上临界磁场

Figure 19. Second peak (SP) effect of three different types of MHLs in three kinds of type-II superconductors: (a) MHL of 2H-NbSe2 shows a sharp SP near upper critical field; (b) MHL of high temperature superconductor Bi-2212 shows a steeper SP at a lower magnetic field (200−500 Oe); (c) SP effect occurs in high temperature superconductor YBCO. The SP effect can appear at high magnetic fields, but the fields are still far below the upper critical field

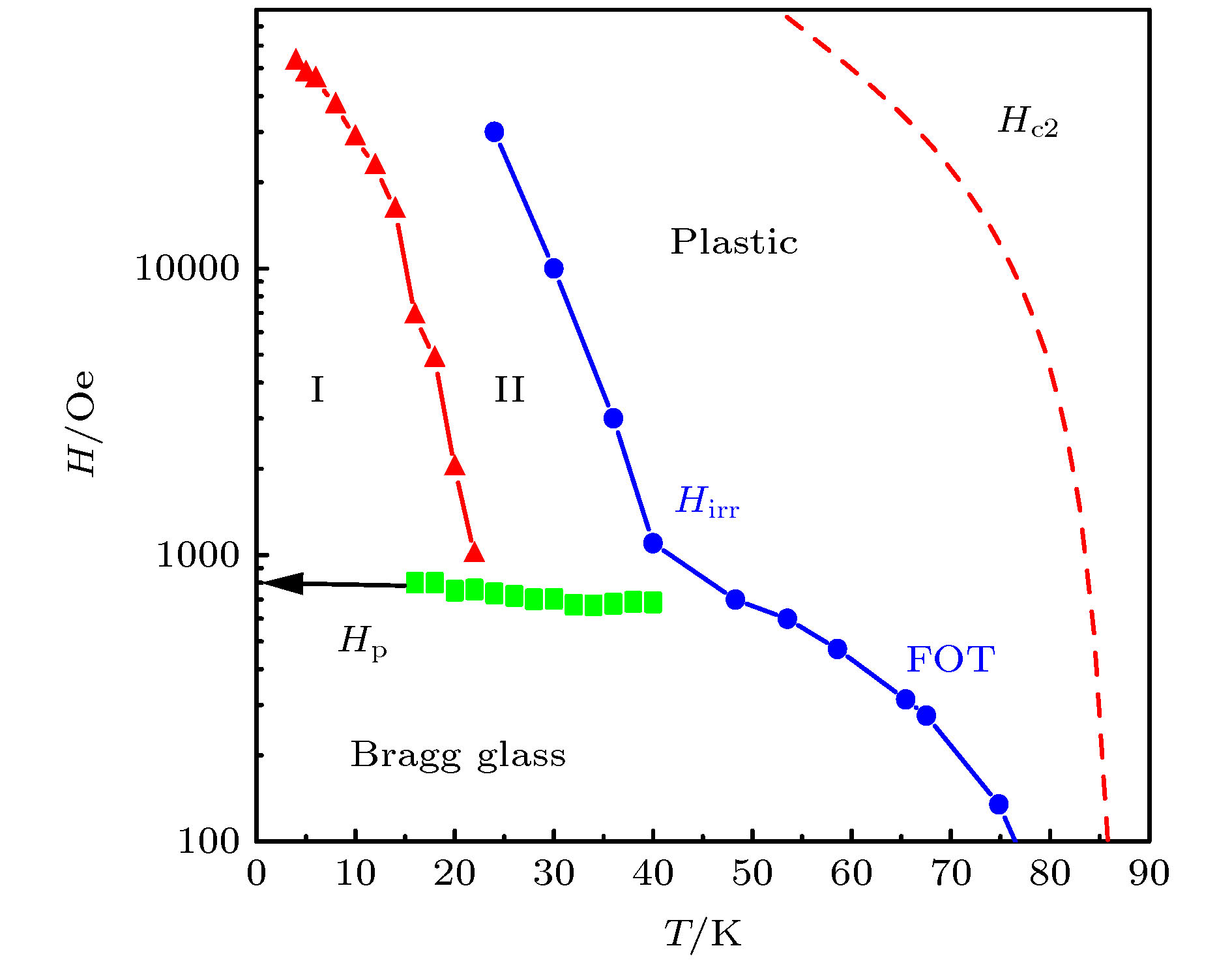

图 20 Bi-2212系统的磁场-温度相图. 在20−40 K温度内, 如方块符号所示的是第二峰出现的位置, 一般认为是在该磁场之下, 磁通系统处于布拉格玻璃态(Bragg glass), 然而超过这个磁场, 磁通系统处于正常的磁通玻璃态 分为耗散低的I区和耗散高的II区. 在40 K以上温区的相变线是磁通一级融化线(FOT, first order transition). 在20 K以下, 通过长时间的弛豫测量, 实际上磁通的布拉格相变仍然能够被观测到

Figure 20. H-T phase diagram of Bi-2212 system. The positions of SP are shown by square symbols, in the temperature range of 20−40 K. It is generally believed that below the magnetic fields marked by the squre symbols, the flux system is in Bragg glass state, beyond that the flux system is in normal vortex glass state. The phase transition line above 40 K is FOT (first order transition) line of magnetic flux. Below 20 K, the Bragg phase transition of magnetic flux can still be observed by long-time relaxation measurement.

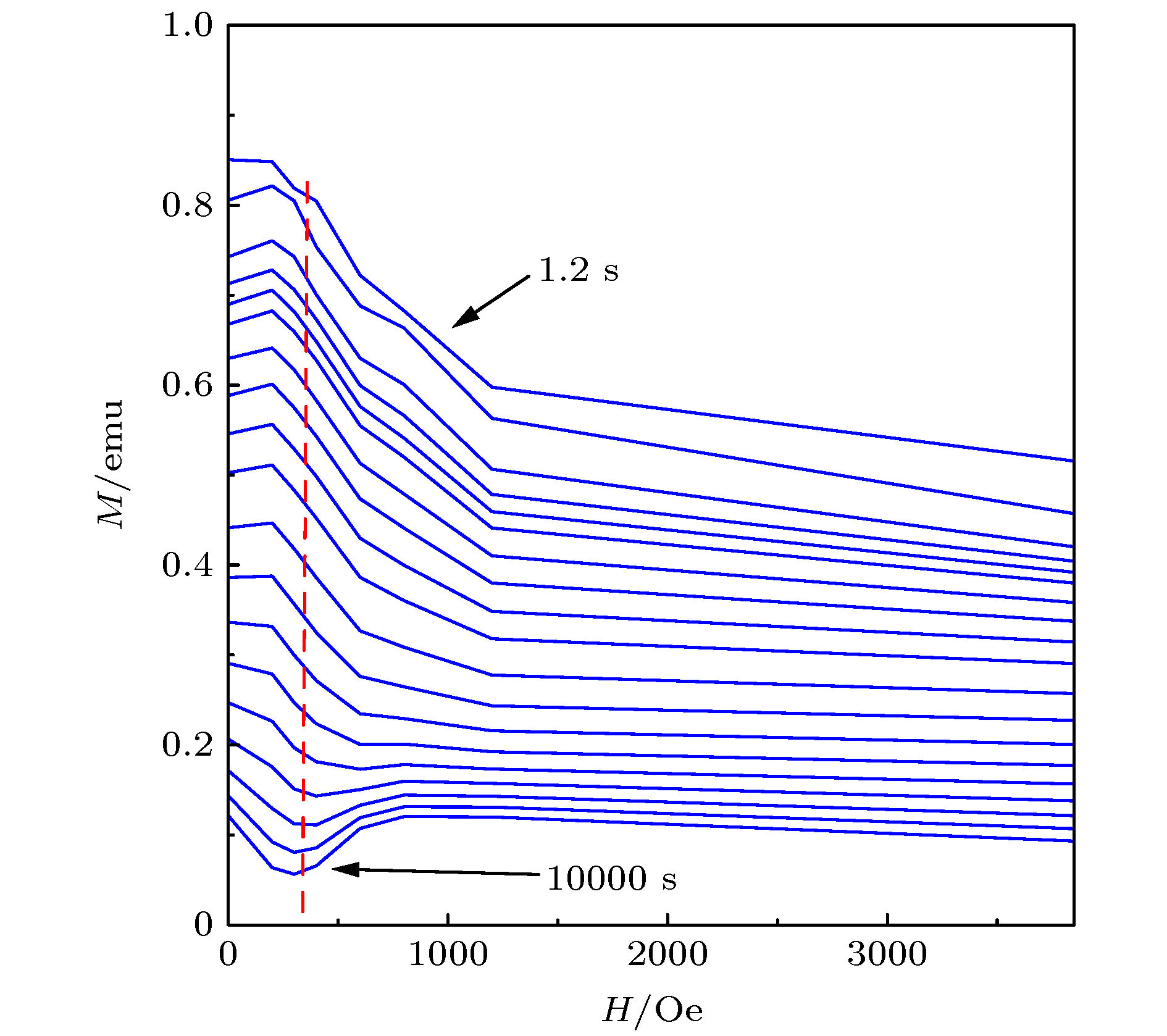

图 21 Bi-2212单晶在T = 5 K温度, 在不同的时间窗口测量到的磁滞回线在降磁场部分随外磁场的变化. 在长时间弛豫以后, 第二峰效应仍然能够呈现出来, 表明布拉格玻璃相变在低于20 K的温区仍然能够发生

Figure 21. MHLs of Bi-2212 single crystal at T = 5 K, measured at different time windows varying with external magnetic field. After a long time of relaxation, the SP effect can still appear, which indicates that the Bragg vortex phase transition can still occur in the temperature range below 20 K.

-

[1] Ginzburg V L, Landau L D 1950 Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 20 1064

[2] Wen H H, Zhao Z X 1996 Appl. Phys. Lett. 68 856

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[3] Cheng W, Lin H, Wen H H, et al. 2019 Sci. Bull. 64 81

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[4] Wen H H, Li S L, Zhao Z X 2000 Phys. Rev. B 72 716

[5] Dew-Hughes D 1974 Philos. Mag. 30 293

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[6] Griessen R, Wen H H, Van Dallen A J J, et al. 1994 Phys. Rev. Lett. 72 1910

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[7] Van Bael M J, Temst K, Moshchalkov V V, et al. 1999 Phys. Rev. B 59 14674

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[8] Bean C P, Livingston J D 1964 Phys. Rev. Lett. 12 14

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[9] Morozov N, Zeldov E, Konczykowski M, Doyle R A 1997 Physica C 291 113

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[10] 张裕恒 2007 超导物理(合肥: 中国科学技术大学出版社)第三版 第94−96页

Zhang Y H 2009 Superconductivity Physics (Hefei: Press of University of Science and Technology of China) pp94−96 (in Chinese)

[11] Bean C P 1962 Phys. Rev. Lett. 8 250

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[12] Wen H H, Wang R L, Li H C, Guo S Q, Yin B, Zhao Z X 1996 Phys. Rev. B 54 1386

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[13] Anderson P W, Kim Y B 1964 Rev. Mod. Phys. 36 39

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[14] Fisher M P A 1989 Phys. Rev. Lett. 62 1415

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[15] Feigel’man M V, Geshkenbein V B, Larkin A I, et al. 1989 Phys. Rev. Lett. 63 2303

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[16] Malozemoff A P, Fisher M P A 1990 Phys. Rev. B 42 6784

[17] Maley M P, Willis J O, Lessure H, et al. 1990 Phys. Rev. B 42 2639

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[18] Thompson J R, Civale L, Marwick A D, Holtzberg F 1994 Phys. Rev. B 49 13287

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[19] Schnack H G, Griessen R, Lensink J G, Wen H H 1993 Phys. Rev. B 48 13181

[20] Wen H H, Schnack H G, Griessen R, Dam B, Rector J 1995 Physica C 241 353

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[21] Blatter G, Feigel’man V M, Geshkenbein V B, Larkin A I, Vinokur V M 1994 Rev. Mod. Phys. 66 1125

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[22] Koch R H, Foglietti V, Gallagher W J, et al. 1989 Phys. Rev. Lett. 63 1511

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[23] Wen H H, Zhao Z X, Wijngaarden R J, Rector J, Dam B, Griessen R 1995 Phys. Rev. B 52 4583

[24] Bardeen J, Stephen M J 1965 Phys. Rev. 140 A1197

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[25] Kwok W K, Paulius L M, Vinokur V M, et al. 1998 Phys. Rev. Lett. 80 600

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[26] Houghton A, Pelcovits R A, Sudbø A 1989 Phys. Rev. B 40 6763

[27] Le Blanc M A R, Little W A 1960 Proc. Seventh Int. Conf. Low Temp. Phys. p198

[28] Pippard A B 1969 Philos. Mag. 19 217

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[29] Larkin A I, Ovchinnikov Yu N 1979 J. Low Temp. Phys. 34 409

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[30] Campell A M, Evetts J 1972 J. Adv. Phys. 72 199

[31] Li S L, Wen H H 2002 Phys. Rev. B 65 214515

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[32] Giamarchi T, Le Doussal P 1994 Phys. Rev. Lett. 72 1530

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[33] Giamarchi T, Le Doussal P 1995 Phys. Rev. B 52 1242

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[34] Nishizaki T, Naito T, Okayasu S, et al. 2000 Phys. Rev. B 61 3649

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[35] Kokkaliaris S., Zhukov A A, de Groot P A J, et al. 2000 Phys. Rev. B 61 3655

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[36] Fruchter L, Malozemoff A P, Campbell I A, et al. 1991 Phys. Rev. B 43 8709

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[37] Wen H H, Zhao Z X, Griessen R 1995 Sci. Chin. A38 717

[38] Hoekstra A F T, Testa A M, Doornbos G 1999 Phys. Rev. B 59 7222

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[39] Blatter G, Ivlev B I 1994 Phys. Rev. B 50 10272

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[40] Nagaoka T, Matsuda Y, Obara H, et al. 1998 Phys. Rev. Lett. 80 3594

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[41] Jin R, Paranthaman M, Zhai H Y 2001 Phys. Rev. B 64 220506

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[42] Wang L M, Sou U, Yang H C, et al. 2011 Phys. Rev. B 83 134506

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

[43] Dorsey A T, Fisher M P A 1992 Phys. Rev. Lett. 68 694; Wang Z D, Ting C S 1991 Phys. Rev. Lett. 67 3618; Vinokur V M, Geshkenbein V B, Feigel’man M V, et al. 1993 Phys. Rev. Lett. 71 1242; van Otterlo A, Feigel'man M, Geshkenbein V, et al. 1995 Phys. Rev. Lett. 75 3736; Ao P 1998 J. Phys. Condens. Matter 10 L677

[44] 闻海虎 2006 物理 16

Wen H H 2006 Physics 16

[45] 闻海虎 2006 物理 111

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

Wen H H 2006 Physics 111

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

Catalog

Metrics

- Abstract views: 20118

- PDF Downloads: 1358

- Cited By: 0

DownLoad:

DownLoad: